Facing the consequences: supporting carbon monoxide awareness week

The Health & Safety Executive deals with dozens of incident investigations a year. Principal Gas Incident Investigation Engineer Steve Critchlow shares insights into an inquiry involving carbon monoxide and what happens when a disaster occurs.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a gas which is produced whenever a hydrocarbon fuel gas such as coal, wood, petrol and gas are burned. The job of engineers is to design, install and maintain appliances and flues such that carbon monoxide production is minimised and that the products of combustion cannot accumulate within an ambient space to create danger.

Thankfully things such as improvement in appliance design, the popularity of CO alarms, and the regulation of landlords means fatal CO incidents involving gas appliances are now quite rare.

However, when it is suspected one has occurred, it is important it is reported quickly to HSE and that a thorough investigation takes place to establish both the causes and the failings that allowed it to happen. It is also important that any lessons learned from such incidents can be promulgated to avoid a repeat.

Lots of registered gas engineers carry out investigations everyday, working out why an appliance isn’t working properly, or on occasions looking into why a CO alarm has sounded.

The difference with a fatal incident investigation is that the investigator must be able to prove what’s happened without repairing or altering the defective CO source (essentially destroying the evidence), and in doing so must record every detail about the site and the history.

All appliances (including other fuels) must be considered in detail as must the general gas safety of the site. The investigator should perform their work in such a way that they can provide details to others several years down the line, including those who might try to discredit or disagree with the findings as a legitimate defence tactic. All whilst coordinating very closely with police investigators.

Thomas Hill lost his life to carbon monoxide at 18 years old

The investigation

Thomas Hill was just 18 years of age when he went on holiday to a rental cottage in the Scottish Cairngorms with his girlfriend and her parents. After a day of walking, he decided to take a bath in the bathroom which was heated by an LPG mobile cabinet heater.

That would be the last time anyone would see Thomas alive. After failing to get him to respond, the family had to break down the bathroom door using an axe to get to him.

The following morning the police called HSE to inform them that a suspected carbon monoxide death had occurred. HSE then called me, requesting I attend the scene to carry out an investigation.

In such circumstances, the urgency of response is often vital. Unless the authorities can be certain the scene will remain secured, and will not be altered, the investigator must get to the scene to record it and to carry out the investigation as soon as possible.

I initially met with police at Brechin Police Station for a briefing on what was known at that time. In these early stages, the police are usually in primacy and will want to know exactly what you plan to do.

They will also be trying to satisfy themselves that the investigator is an expert and will quiz you on your experience and qualifications. These qualifications involve not just my Gas Safe registration, but also my GL/8 and CMDDA1 investigators qualifications, my MSc and my experience as working as an expert witness.

In these early stages, the cause of death isn’t confirmed; it can often take many weeks or even months for blood toxicology to prove CO was the cause of death. That was the case here, but CO was suspected due to the sudden nature of the death and because there was a gas heater in the bathroom.

On arrival at the scene, I examined all rooms in the two-bedroom cottage as well as outside for any potential sources. I identified three Immediately Dangerous defects and twelve At Risk defects.

This immediately creates a sense that the gas installation at the site had not been subject to competent installation and inspection and should the HSE need to consider whether a duty holder has been negligent. Such peripheral evidence can be extremely important.

The defects included things such as cabinet heaters in rooms too small and without ventilation, an LPG caravan refrigerator that should be flued to outside, discharging its products of combustion into the room, a gas leak, and five butane cylinders stored indoors.

Those defects included a mobile LPG cabinet heater in the bathroom. The Gas Safety (Installation and Use) Regulations 1998 tell us that it’s a breach of the law to install any gas appliance other than one which is room sealed into a bathroom.

The IGEM/G/11 - Gas industry unsafe situations procedure tells us that a flueless appliance in a bathroom must be treated as being Immediately Dangerous. The bathroom had no ventilation provision when the relevant British Standard for the appliance states it should have 56 cm2 and the room had a volume just a quarter of the size it should have been. In addition, I observed a hairline crack on the ceramic plaque burner of the gas heater.

Despite these defects, the inspection must consider every possible source. Each appliance was operated and inspected, and the gas tightness and working pressure was examined. This included a solid fuel open fire in the living room. As an investigator I carry HETAS qualifications and OFTEC qualifications to enable me to work on all installations in a property, not just the gas ones.

Testing

Ultimately a “simulation test” was performed. This involves operating a suspected dangerous appliance in the conditions it was found in and showing whether any resulting ambient carbon monoxide could accumulate to potentially fatal levels.

IGEM/GL/8 - Reporting and investigation of gas-related incidents advises that exceeding 200 ppm may pose safety risks to investigators and other occupants and should be sufficient to establish the potential for causing death.

As this was a detached property where we could control access, we had the ability to take levels much higher although this involved creating a risk assessment and safe system by which we could remotely isolate the gas and could ensure fumes were dispersed before personnel could enter.

Five combustion analysers were used, including one that could measure up to 100,000 ppm. This was placed at the burner to capture the peak levels coming off the appliance.

The other four analysers log a measurement of all combustion products every second so that the investigator has detailed evidence of exactly what was happening and when.

All of my measurement kit must be calibrated, and I will personally test the analysers with a span gas before and after a serious investigation to ensure their accuracy has not drifted since calibration.

An interesting quirk of this investigation was that the living room was illuminated by two gas mantles (gas lights). These each produced over 550 ppm of CO when an analyser was placed above them.

To rule them out, I left them operational during the simulation test and could therefore prove they were not involved as only trace levels of CO accumulated in the living room (only) during the test.

Whilst the CO concentration was high at the mantle, as the gas rate was extremely low,the volume of CO produced was equally low, therefore creating only trace levels when it was diluted into the room.

The probes of analysers were positioned at the appliance, at the bathroom centre at head height, at the deceased person’s position, in the hallway centre at head height, and in the living room at head height.

CO tends to leave the appliance and move towards the ceiling due to its buoyancy before returning to lower levels as it cools – typically at the rear wall of a room. Unless the atmosphere is turbulent it tends to form and move as a cloud rather than dispersing freely into the air.

It’s therefore possible to miss it if the probes are placed without a good deal of thought. I once measured far higher CO levels in an upstairs bedroom than I did just one metre away from the operating flueless appliance in the downstairs kitchen due to a very high ceiling, the CO passing above my probe and moving upstairs.

The analysers were placed outside in fresh air, connected by hoses to probes mounted on tripods in the desired measurement locations. A means of getting the hoses out of the house without creating unrepresentative ventilation needs to be devised, as does a means for rapidly ventilating the area at conclusion of the test.

The simulation test is preceded by a period of testing this atmosphere in the dwelling without the appliance operating. This establishes a base level, demonstrating whether there is any CO in the house before the test and whether any CO is migrating into the house from elsewhere.

My initial simulation test was performed for over 1.5 hours, which is considerably longer than the deceased was reported to have been in the bathroom. At the conclusion of testing, the highest ambient CO concentration was 221 ppm at the centre of the bathroom. Oxygen was depleted down to 18.5 per cent from 20.9 per cent.

The results indicated that the operation of the appliance in the small unventilated bathroom was producing very high ambient CO and was reducing oxygen which can be damaging to health, but that the figures measured would be unlikely to cause death in time the deceased was reported to have been exposed.

At this stage CO had not been medically proven as cause of death and our testing indicated that whilst the deceased would have been exposed to elevated CO, this wouldn’t directly cause death.

Importantly, both the police and HSE are able to take items into possession for secure storage, and to issue notices to leave a property undisturbed. We could therefore take the heater away and retain the option to revisit should medical tests show CO to have caused death.

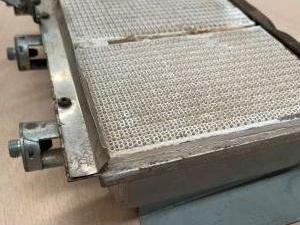

A typical plaque burner from an LPG heater

An example of a plaque burner is shown in the photograph. Gas is passed through an injector at the base of a primary airport. The injection causes gas pressure to drop which allows fresh air (including oxygen) to push in via the primary airport.

The resulting gas and air mixture forms in the metal box at the rear of the ceramic plaque but importantly cannot combust there. The small holes in the plaque allow the gas and air to pass through to where gas can combust in open air, and hence receiving plentiful secondary oxygen.

Crucially the flame cannot pass through the holes to the rear of the plaque because the plaque acts as a flame arrestor. I have already mentioned that I initially noted a small crack in the burner.

Such cracks can be very dangerous as they can allow the flame to pass through the burner, although this did not happen in my initial simulation test.

My subsequent testing at the HSE Science and Research Centre in Buxton showed that the burner plaque would intermittently allow the flame to pass through.

Typically, it would do this after several minutes of operation as the plaque warms up and expands. A bang followed by loud roaring combustion would occur and the flames impinged on the metal box, and CO levels exceeding 40,000 ppm would result.

This was communicated to the police and HSE, and when medical evidence finally confirmed Thomas had died of CO poisoning, I was able to revisit the site and perform a second simulation test. This time room centre CO levels exceeded 1000 ppm within 12 minutes of lighting the appliance.

The results

I then issued a 16,000-word written incident report to HSE outlining not only the cause of the incident, but all the defects found, and the relevant legislation relating to the installation. The report provided details on all the measurement kit used, how the measurements were performed, and all standards and regulations etc were referenced.

At this point, the HSE can commence its investigation by collecting documentation and interviewing witnesses. They established that the property was owned by a business that rented out over 80 other properties, but also that they rented this particular property to just one person, who himself then sublet it as a holiday business.

They also established that a registered gas engineer had worked in the property for many years at the request of both the landlord and the business operator, but that his duties had only extended to “servicing the boiler” and providing LPG.

The cabinet heater in the small unventilated bathroom

He had seen the LPG heaters but never commented on them. He had never been asked to perform an annual landlord’s gas safety inspection and equally had never suggested to the landlord and business operator that one was required. The HSE investigation found that no landlords gas inspection to comply with GSIUR Reg 36 had ever been performed.

The HSE also found out that the previous holiday makers had experienced stinging eyes and a CO alarm going off in the kitchen after using the heater in the bathroom. They had reported this to the business operator, but this resulted only in the gas engineer changing the LPG bottle.

I then had to compile a second report to fulfil the role of “expert to the court”. This 12,000-word document provided detailed written opinion to assist the court with its enquiries. I had to define the roles and responsibilities of the landlord, business operator and the gas engineer, and I concluded each had legal failings which ultimately meant opportunities to prevent the fatal incident were not taken.

The court would ask questions such as “should the gas engineer have recognised the danger of the heater”, and “when would the crack in the burner have occurred”. Subsequently I produced a third report which considered whether a CO alarm in the property had ever been tampered with and whether it was functional.

Over six years after the incident, I appeared at a fatal accident inquiry to give evidence as an expert for a five day hearing. The reader can therefore see the importance of accurate detailed notes and reports, and copious photographs, without which it would not be possible to accurately assist the court.

Ultimately the landlord was fined £120,000 for their health and safety failings and the business operator was fined £2,000.

Such cases are very challenging and emotional. While nothing can bring the deceased back or prevent the tragedy the families have suffered, being able to provide answers to the family so they understand what’s happened and why is ultimately a privilege.

Since this case, I have been telling this story in the hope that gas engineers are increasingly mindful of their duties in relation to unsafe appliances they may see whilst working on others, and so they understand the danger presented by a crack to a plaque burner.